Letter addressed to William Kerr at the General Post Office at Edinburgh on the protest in Glasgow, 3 April 1820. It linked the idea of a general strike to reform, and anticipated the Chartist ‘National Holiday’ and general strike plans of 1839 and 1842. Stopping a mail coach to signal that the insurrection had begun elsewhere was a common device.

(Catalogue reference HO 33/2/33 f155)

Transcript

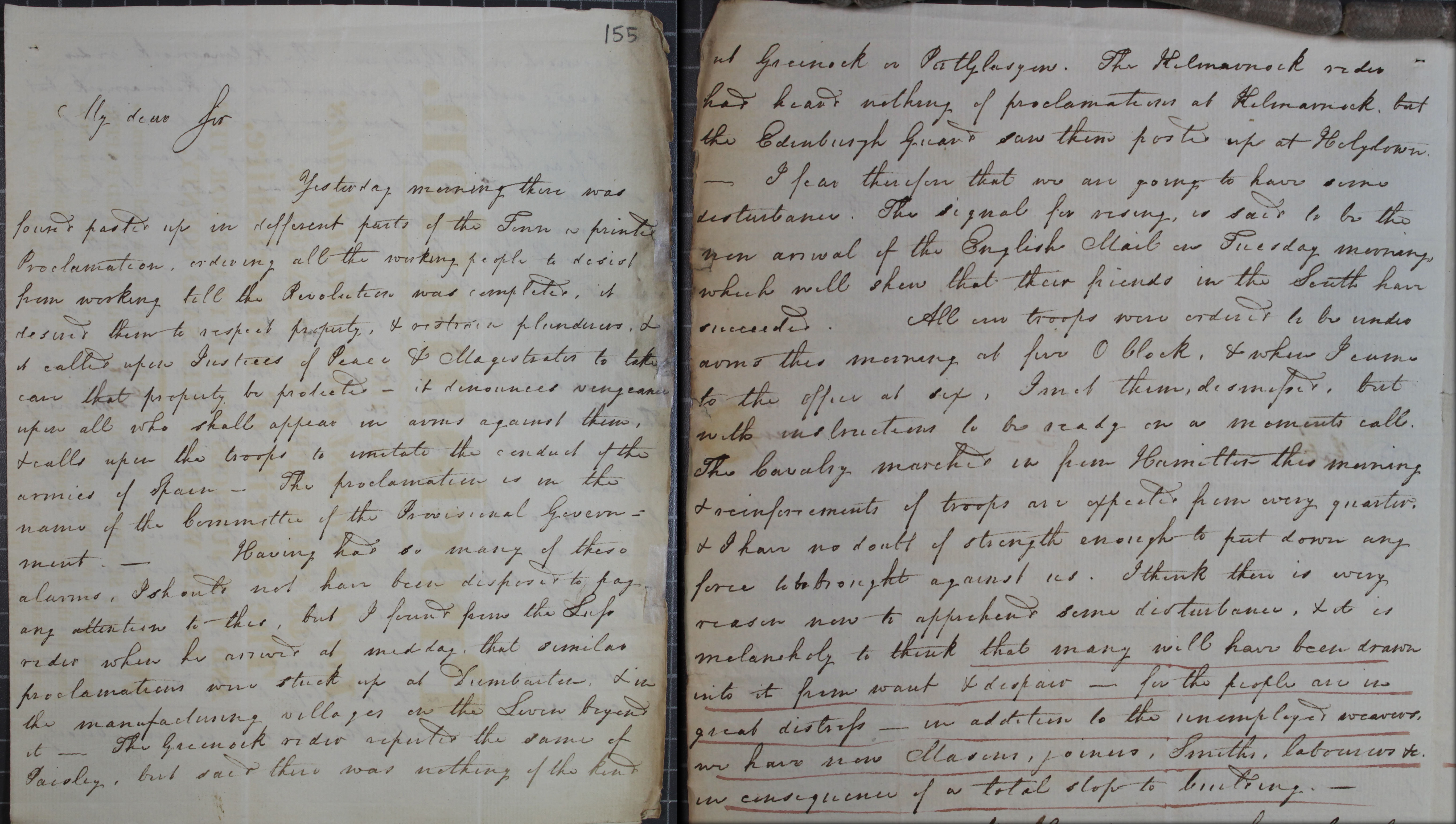

My Dear Sir,

Yesterday morning there was found posters up in different parts of the Town in printed Proclamation, ordering all the working people to desist from working till the Revolution was complete, it desired them to respect property and restrain plunderers and it called upon Justices of the Peace and Magistrates to take care that property be protected — it denounced vengeance upon all who shall appear in arms against them, and called upon the troops to imitate the conduct of the armies of Spain. The proclamation is in the name of the Committee of the Provisional Government —Having had so many of these alarms, I should not have been disposed to pay any attention to this, but I found from the Post rider when he arrived at midday that similar proclamations were stuck up at Dumbarton and in the manufacturing villages on the Leven [river] beyond it. The Greenock rider reported the same of Paisley, but said there was nothing of the kind

(ii)

at Greenock or Port Glasgow. The Kilmarnock rider had heard nothing of proclamations at Kilmarnock, but the Edinburgh Guard saw these posters up at Holytown. I fear therefore that we are going to have some disturbance. The signal for rising is said to be the non-arrival of the English Mail on Tuesday morning which will show that their friends in the South have succeeded. All our troops were ordered to be under arms this morning at five o’clock, and when I came to the office at six, I met them dismissed, but with instructions to be ready on a moment’s call. The cavalry marched in from Hamilton this morning and reinforcements of troops are expected from every quarter and I have no doubt of strength to put down any force to be brought against us. I think there is every reason now to apprehend some disturbance and it is melancholy to think that many will have been drawn into it from want and despair — for the people are in great distress — in addition to unemployed weavers, we have now masons, joiners, smiths, labourers etc. in consequence of a total stop to building.

…