How much can police records reveal about the lives of LGBTQ+ people in the past? In the below video, Hannah Carter and Victoria Iglikowski-Broad introduce the file CRIM 1/387 and what it can tell us about LGBTQ+ history in 1920s London. Stefan Dickers from the Bishopsgate Institute also showcases some of their extraordinary collection relating to LGBTQ+ British history.

Teacher notes

This film and set of resources is suitable for an assembly, form time or a lesson on LGBTQ+ history. The film is around 12 minutes in length. Please consider answering this survey after using the video, as it will help us develop future education resources.

There is an accompanying PowerPoint presentation with questions to facilitate pupil discussion and teacher notes.

When discussing key developments in the 20th century for LGBTQ+ people, teachers may want to use these recommended timelines:

- Stonewall: Key dates for Lesbian, Gay Bi and Trans Equality

- British Library: A timeline of LGBTQ communities in the UK

Bobby Britt, whose story is explored in the film, lived from 1900 to 2000 and therefore would have witnessed huge changes. Teachers could ask students to identify different types of changes, e.g legal or social. Or pupils could judge which change/s would have had the biggest impact on LGBTQ+ people’s lives.

‘Keeping a disorderly house’, Fitzroy Square, London, 1927. CRIM 1/387 (1)

Teachers may want to use the documents included in the resource pack. Students could analyse the document in more depth considering questions like:

- What type of document is it?

- Who produced it?

- Who was the audience?

- Why was it made?

- How much does it reveal about life for LGBTQ+ people in the past?

Questions to consider for class discussion (included on PPT):

- What can The National Archives documents reveal about the lives of LGBTQ+ people in the 1920s?

- What did you find shocking or surprising?

- Why is it important to also go to other archives/museums to learn about LGBTQ+ history?

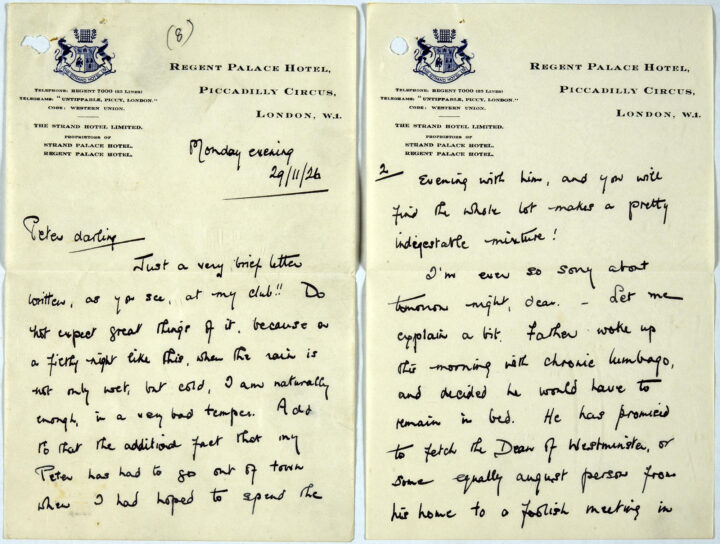

‘Letter from Eric to Peter, evidence in a case of keeping a disorderly house’, 29 November 1926. CRIM 1/387 (1 and 2 of 6)

You could explore with students why stories about LGBTQ+ women and transgender people are harder to find within The National Archives. For instance, this resource explores documents that exist due to the targeting of gay men by police, while love between women was less criminalised. There are resources that can extend students’ learning about the history the broader LGBTQ+ spectrum included in the ‘Useful links’ section of the resource.

Background

The film explores what documents at The National Archives can reveal about LGBTQ+ history. It focuses on the story of a basement flat at 25 Fitzroy Square, the home of Bobby Britt, a dancer on the West End stage. He would hold parties for a small group of his working-class friends. One of these parties was raided by the police in 1927 under accusations of being a disorderly house.

We know about these gatherings due to extensive undercover police surveillance and documents that the police recovered from the flat. The flat was being observed because, at these gatherings, men would have relationships with other men. This was an era when sexual acts between men were both criminalised and socially unacceptable in wider society.

While it was never illegal to be gay, many of the associated practices were criminalised. This included sexual behaviour, being in certain spaces, and physical appearance – for instance, men wearing makeup. For example, The National Archives’ collection contains pieces of blotting paper used to forcibly lift makeup off the faces of men who were arrested. In just going about their daily lives, men who had relationships with other men could be arrested, prosecuted and imprisoned. It was not until the 1967 Sexual Offences Act that real legal change meant that LGBTQ+ people’s lives were less criminalised.

The CRIM 1/387 document file includes a range of different types of primary sources, including annotated photographs, a list of exhibits, police surveillance notes and even seized love letters between men. Despite being gathered by police, these documents can give a valuable insight into the lively atmosphere of Fitzroy Square and even provide rare voices of LGBTQ+ people in the 1920s.

However, the film and resources also explore how important it is to use other collections to learn about LGBTQ+ history. Documents from the Bishopsgate Institute are included within this pack. These include diary entries written by William Mahoney, documenting his life with his partner Doug in the 1940s. The Bishopgate Institute’s collection can provide a more personal insight into the experiences of LGBTQ+ people in the past. For instance, they hold the log books for Switchboard, detailing conversations with people who rang this LGBTQ+ helpline.

Note that we are using the term LGBTQ+ here as an umbrella term, but many of the people discussed would not have had this language available to them at the time, and would have used contemporary language to describe their sexuality.

Useful links

The National Archives:

Blogs:

- ‘Corrupting Public Morals?’ Fitzroy Square and Queer Desire by Vicky Iglikowski-Broad

- ‘Kisses and kind thoughts’: Queer networks and letters between men by Vicky Iglikowski-Broad

- ‘Bohemian, broad-minded, unconventional.’ What was it like to be queer in the 1920s? by Vicky Iglikowski-Broad

- HIV/AIDS and the LGBTQ+ community: Education, care and support by Mollie Clark

- Dr James Barry: The importance of archival discoveries by Mollie Clark

Other links

Timelines:

- Stonewall – Key dates for Lesbian, Gay Bi and Trans Equality

- British Library – A timeline of LGBTQ communities in the UK

Useful websites:

- Bishopsgate Institute

- Historic England – Pride of Place: England’s LGBTQ Heritage

- Stonewall Education Resources

- Switchboard

- London Metropolitan Archives

- Queer Britain

- LGBT collections (the Hall-Carpenter Archives) at the LSE

Download assembly PowerPoint