Download documents and transcripts

Teachers' notes

The purpose of this document collection is to allow students and teachers to develop their own questions and lines of historical enquiry on the political and social aspects of 1950s Britain. The documents themselves are arranged according to theme, so that sources are grouped together rather than following a strict chronological order.

Some of the themes include:

- the economy

- rationing

- housing

- the National Health Service

- race relations

- cultural life

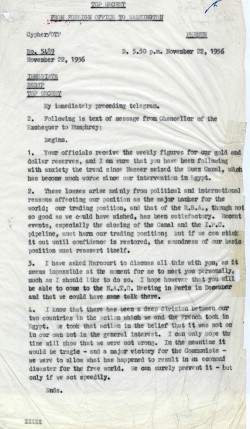

- the Suez crisis

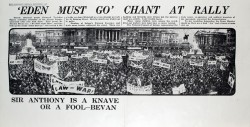

- nuclear protest

Please also note that in a couple of cases sources relating to the same topic appear in the same popup window so it is necessary to scroll from side to side to explore them in detail.

Students could work with a group of sources or source type on a certain theme or linked themes. The documents should offer them a chance to develop their powers of evaluation and analysis and support their course work. Alternatively, teachers may wish to use the collection to develop their own resources or encourage students to ‘curate’ their own ‘exhibition’ of the most significant sources on the topic.

Students could also use more documents from our Cabinet Papers website. For example, there are cabinet papers relating to the death penalty, taxation under the conservatives, immigration and the National Health Service. Finally, there is an opportunity to consider film sources as interpretations of these events in relation to the documents by following the links to Pathé and the BFI provided here.

Connections to the curriculum

These documents can be used to support any of the exam board specifications covering the political, social and cultural aspects of 20th century British history, for example:

AQA: GCE History

A2 Unit 3: The State and the People: Change and Continuity

HIS3J: The State and People: Britain, 1918-1964

HIS3M: The Making of Modern Britain, 1951-2007

Edexcel: GCE History

E2 Mass Media, Popular Culture and Social Change in Britain Since 1945

OCR: GCSE History B

Unit A972: British Depth Study: How far did British society change, 1939-1975?

OCR: GCE History A

Unit F961 Option B Study Topic 6: Post-War Britain 1951-94

Introduction

by Dominic Sandbrook

For many people, the 1950s were a golden age. ‘Let’s be frank about it,’ declared Harold Macmillan in July 1957: ‘most of our people have never had it so good.’ Almost immediately the Prime Minister’s words became a symbol of the age, capturing the optimism of a nation basking in the sunshine of the affluent society. Yet like so many political quotations, they are often misunderstood. Macmillan meant them not as an expression of complacency, but as a warning. ‘What is worrying us,’ he went on, ‘is “Is it too good to be true?” or perhaps I should say “Is it too good to last?”‘

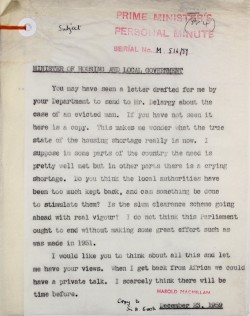

It is no wonder that we rarely remember what Macmillan really meant by his famous phrase. Even at the time, most people preferred to enjoy the fruits of consumerism rather than worry about the future. At the beginning of the 1950s, after all, Britain had been threadbare, bombed-out, financially and morally exhausted. Its major cities were still bombsites, it was almost impossible for many families to borrow money, rationing was harsher than ever, and there was an acute shortage of decent housing. Yet within less than ten years, everything had changed; indeed, perhaps more than any other post-war decade, it was the 1950s that transformed Britain’s social and cultural landscape.

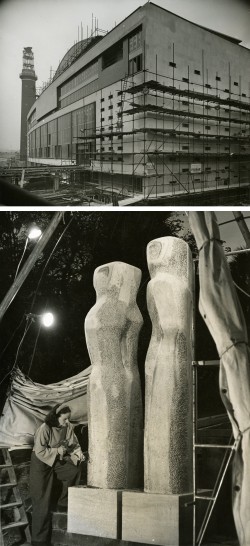

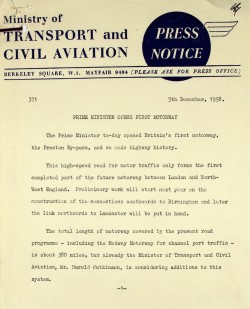

As the economy began to boom, wages soared and unemployment almost disappeared, everyday life became more comfortable. Towns and cities were reshaped by council estates, tower blocks and shopping centres. Supermarkets transformed families’ shopping habits, while the television began to make inroads into their leisure time. Millions of people tuned in especially for the Coronation in 1953, with neighbours crowding into the houses of those lucky few who owned or rented sets. Inspired by the groundbreaking Festival of Britain, the design of the typical home, self-consciously upbeat and forward-looking, marked the transition to what contemporaries optimistically called the Space Age. And even the nation’s roads reflected the new spirit, symbolized by the opening of Britain’s first motorway, the Preston bypass, in 1958.

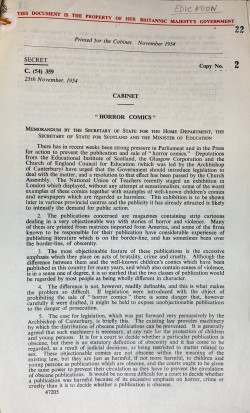

It was this extraordinary economic growth that paved the way for everything that followed. In particular, the youth culture of the day was entirely based on the emergence of a new teenage generation. Better housed and educated than ever before, the generation of Cliff Richard and Adam Faith enjoyed unprecedented financial independence. They watched television and read comics; they bought records and danced to rock music. In their carefree hedonism and economic assertiveness, they often shocked their elders: when ‘Rock Around the Clock’ reached Britain in 1955, there was much anguished talk of ‘rock and roll riots’. In truth, though, most teenagers were fairly conservative, individualistic and materialistic – just like their parents.

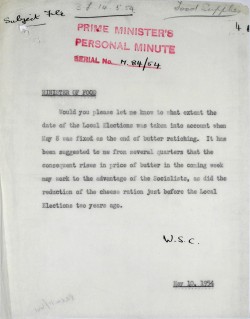

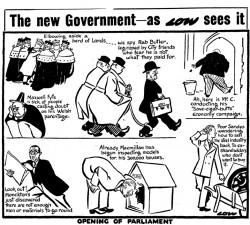

Yet as the reaction to rock and roll suggests, there was a thick vein of anxiety beneath the surface of the affluent society. Despite the apparent complacency of Winston Churchill, Anthony Eden and Harold Macmillan, many politicians were worried about Britain’s economic prospects. And though historians still argue about the extent of the famous ‘Butskellite’ consensus, epitomized by the moderate figures of R. A. Butler (Conservative) and Hugh Gaitskell (Labour), Britain’s political direction remained the stuff of ferocious debate. Inside the Labour Party, Aneurin Bevan’s resignation over the imposition of prescription charges in 1951 set the tone for a decade of bitter faction fighting. Inside the Tory Party, meanwhile, the abortive ‘Robot’ scheme to set the pound free a year later offered a hint of the emerging free-market doctrines that would eventually culminate in Thatcherism.

All the time, Britain’s world status was changing rapidly. As one colony after another chose independence, the Empire was slowly fading into history, while the fiasco of the Suez Crisis in 1956 seemed to mark the end of Britain’s days as a world power. Massive Commonwealth immigration, which transformed the face of the nation’s cities, alarmed many working-class voters, while the Notting Hill riots in 1958 exposed the ugly face of everyday racism. With violent crime rapidly increasing, many commentators warned of rising ‘juvenile delinquency’. And overshadowing everything else was the looming threat of nuclear war, which prompted some people to join the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. Today, CND’s marches are some of the best-remembered events of the decade. Still, the truth is that they only attracted a minority. Most people preferred to spend their weekends shopping for a new sofa instead.

Dominic Sandbrook is the author of ‘Never Had it So Good: A History of Britain from Suez to the Beatles’.

External links

- British film in the 1950s

Ealing and Hammer, Rattigan and Redgrave; the BFI looks at the decade in film - British Pathe

Use the site to view contemporary newsreel footage from home and abroad - Marriage in the 1950s and 60s

The BBC Archive looks at social change for postwar women